Academic Integrity#

Note

Source Code: teach_online/academic_integrity.md

In this chapter, we will be discussing ways to maintain Academic Integrity in online assessments. Some content in this chapter may overlap with other chapters (e.g. if we discuss Academic Integrity when we introduce specific online assessment tools), but this chapter will be structured in a way that is hopefully agnostic to specific tooling. This chapter draws heavily from Eaton [23], a resource I strongly recommend for anyone curious about Academic Integrity.

Deterrence vs. Detection#

Before discussing any techniques for maintaining Academic Integrity, we first need to present some foundational terms and concepts. There are two key terms that describe two closely-related yet distinct concepts: deterrence and detection. Detection is the act of correctly identify cases of cheating (e.g. by comparing submissions, witnessing copying, using plagiarism detection tools, etc.), whereas deterrence is the act of stopping/preventing people from cheating [24] (e.g. by proctoring/monitoring students, convincing them they will get caught and receive a severe penalty, etc.).

Exams#

One of the most frequent concerns I have heard regarding maintaining Academic Integrity in online courses is with respect to online exams. Instructors often rely on exams to serve as comprehensive evaluations of student mastery, and ensuring the integrity of this form of evaluation is an important goal.

Remote Proctoring#

When administering remote exams, especially in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, many instructors relied on remote proctoring, in which students take an exam on a computer while being supervised by a person and/or computer software [24]. The idea behind remote proctoring is intuitive: students are typically proctored when they take in-person exams, so they should be proctored when they take remote exams… Right?

Well, the situation might not be so simple. In a proctored in-person exam, all students leave their homes to meet at a specified location to take their exam (commonly a lecture hall or some other facility at their university). In remote proctoring, however, most students take the exam from their home (typically in a personal space like their bedroom) [25]. Taking an exam is already stressful enough, but being watched over the internet contributes to test anxiety (as well as exacerbating other equity issues, such as internet literacy, access to reliable technology and a dedicated study space, etc.) [26]. Is this infringement of student privacy a necessary evil [27] to ensure Academic Integrity?

Dawson [24] provides an excellent exploration of the evidence for and against the use of remote proctoring, so I highly recommend reading it thoroughly. Here, I will briefly summarize the key points of discussion:

With respect to deterrence of cheating:

Many studies split students into “proctored” vs. “unproctored” groups and evaluate student grades across groups

Many of these studies find lower grades in the “proctored” group

With respect to detection of cheating:

With respect to privacy:

Some students feel uncomfortable, but others are actually fine with being proctored remotely [27, 34]

There are also privacy concerns regarding how proctoring companies store/use student data [39]

It can contribute to the culture of surveillance and to the acceptance of surveillance in other realms [40]

Again, I strongly encourage you to read Dawson [24] in its entirety, as it does an excellent job presenting the research regarding the pros and cons of remote proctoring. If, after reading the relevant research and weighing the pros and cons, you decide that you want to conduct remote proctoring in your course, the following services may be of interest:

ProctorU (now Meazure Learning) has live proctors monitor students in real-time

Proctorio records students while they take exams and performs automated software-based video analysis as well as live human review

Depending on the size of your class, your course staff can proctor students live using Zoom or similar video conferencing services

Exam Similarity Detection#

Beyond just proctoring students during the exam, another technique for detecting cheating is to look for similarity in exam responses. The logic here is intuitive: if two students have suspiciously similar exams, they may have cheated on the exam (e.g. collaboration, or one student copying from the other). For open-ended questions that require free form (e.g. essay) responses, detecting exam similarity is easy: just use a service like Turnitin: overly identical sentence structure and word choice is a strong indicator of cheating.

However, what about exams with multiple choice, short answer, numerical, etc. questions? As a pedantic Computer Scientist, I will pose a question that sounds simple but is actually deceptively complex: how exactly do we define exam “similarity”?

Fig. 2 You, when you realize the true complexity of the question.#

At a glance, one might define “similarity” as the proportion of questions both students responded to with the exact same answer: if two students collaborate on an exam, we expect them to have identical (or near-identical) answers… Right? Sure, that’s true: students who collaborate will likely have many identical answers. However, the reverse is not necessarily true: assuming the instructor wrote a fair exam, students should hopefully converge towards the correct answers, meaning two students who did really well will also have a lot of identical answers (the correct answers). In the world of statistics, we call this a non-identifiable model: two different input scenarios (collaborate vs. both did well on the exam) result in the same outcome (high proportion of identical answers), so the proportion of identical answers may not be super informative in cheating detection on its own.

Okay, so shared identical correct responses might not be super informative, but what about shared incorrect responses? If two students make the exact same mistake on multiple questions, that could be suspicious. But what about True/False questions? If two students get the question wrong, they must have the same wrong answer: there’s only one possible wrong answer! As an extension of this line of thinking, even if there are multiple possible wrong answers, some wrong answers will be more frequent than others: the same misconception will likely lead to the same wrong answer, and more common misconceptions will lead to more frequent wrong answers. In other words, the uniqueness of a shared wrong answer is interesting.

In Moshiri [41], we proposed the Moshiri Exam Similarity Score (MESS) that can be calculated for a given pair of students \(x\) and \(y\) as follows:

For a single question, define the “score” for that question as one of the following:

If either student (or both) got the question right, the score is 0

If both students got the question wrong, but they put different wrong answers, the score is 0

If both students put the same wrong answer, the score of that question is the proportion of students who put a different wrong answer

In other words, if \(n\) students got the question wrong, but only \(k\) students put this exact wrong answer, the score of this question is \(\left(n-k\right)/n\)

If every student who got the question wrong put this same wrong answer (i.e., \(k=n\), e.g. True/False), the score would be 0

If these students were the only students to put this specific wrong answer (i.e., \(k=2\), the score would approach 1

Calculate the score of every question on the exam as described above, take their sum, and normalize by dividing by the number of questions

In other words, the overall exam score is the average of the scores of the individual questions

The calculation description above is intentionally written colloquially (rather than using formal mathematical notation) in an attempt to keep this resource reasonably accessible across disciplines, but the formal mathematical definition of MESS can be found in Moshiri [41].

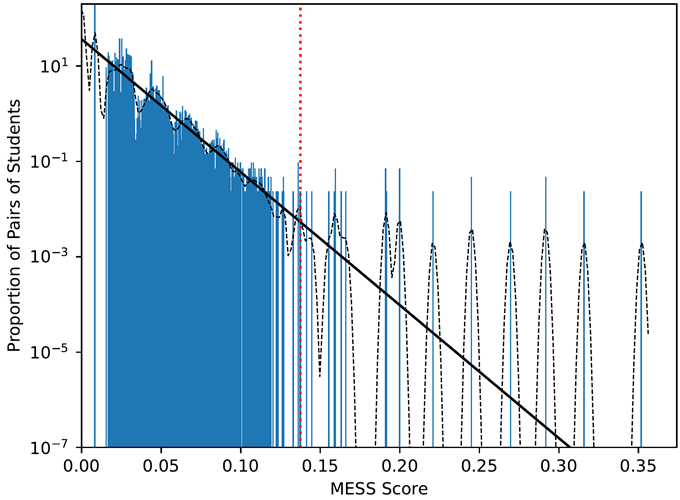

Now that we’ve defined MESS, what can we actually do with it? If we calculate MESS on all pairs of students in the class, we can assume that the vast majority of MESS scores we calculate will not be between cheaters. We can validate this assumption with a simple thought experiment: in a class of n students, if every single student paired up with another student to collaborate on the exam, we would have n/2 cheating pairs of students out of n(n–1)/2 total pairs of students. In a class of n = 100 students, we would have 100/2 = 50 cheating pairs and out of 100(99)/2 = 4,950 total pairs of students (just over 1% of all pairs of students). Thus, we can use the distribution of all pairwise MESS calculations as an approximation of the null distribution (null hypothesis = “MESS score resulted from no collaboration”), and we can try to identify collaboration by looking at outliers of this distribution (e.g. perform one-sided tests of statistical significance, as well as multiple hypothesis test correction). An example plot of a MESS distribution can be found in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Distribution of all pairwise MESS calculations in a 500-person Advanced Data Structures course (log-scale). A histogram is shown as blue bars, a Kernel Density Estimate (KDE) is shown as a dashed black curve, and the Probability Density Function (PDF) of a best-fit Exponential distribution is shown as a black line. Statistical significance tests were conducted on all scores to the right of the dashed red line.#

However, there are a handful of limitations of this method:

If two students happen to make the same very unique mistake, it could artificially give them a very high similarity score

This is a feature, not a bug: if two students make the same extremely unique mistake, an instructor should investigate

If two students are very successful in their cheating, this method would fail to detect their collaboration

There simply won’t be enough incorrect responses to detect similarity

In the extreme, if they achieve perfect scores through collaboration, their MESS calculation will be 0

If two cheating students have many identical wrong answers, but they happen to pick popular wrong answers, their score will be artificially low

Thus, this method is specific (i.e., high MESS typically implies collaboration), but not sensitive (i.e., it can miss true cases of cheating)

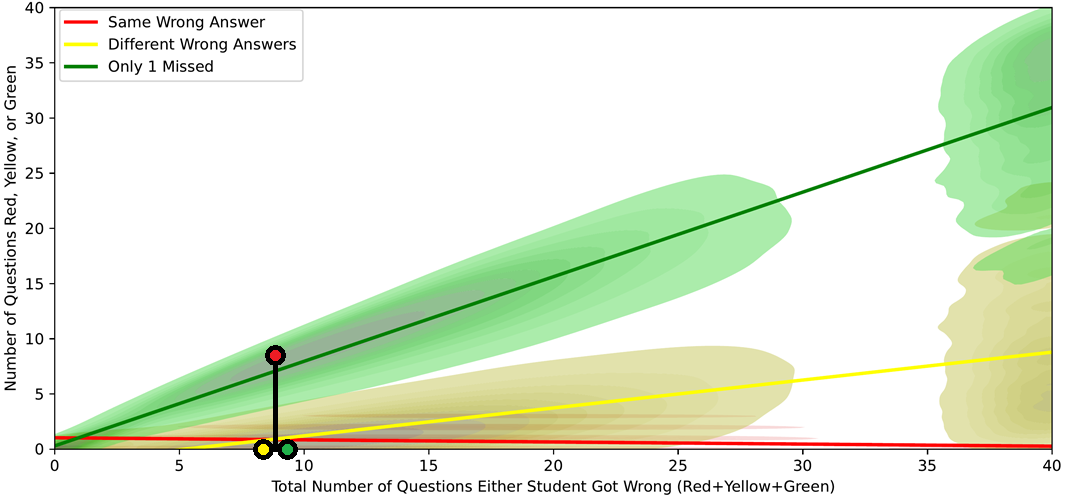

MESS gives us a way of looking at the uniqueness of shared incorrect responses, but we can also gain interesting insights from the number of shared incorrect responses in the context of all incorrect responses they submitted. Specifically, expanding on Moshiri [41], while performing all MESS calculations, we can also count the following for every pair of students (the colors are arbitrary and aim to align with “scarier color” = “more suspicious”):

Red Count = The number of questions both students missed with the exact same wrong answer

If students collaborate, we expect a disproportionately large number of identical wrong answers between them

Yellow Count = The number of questions both students missed, but with different wrong answers

If students collaborate, we might expect them to put the same wrong answer, so Yellow questions could be evidence against collaboration

However, if students collaborate and are torn between two potential answers, one might guess one answer, and one might guess another, so Yellow questions could be evidence supporting collaboration

Thus, overall, Yellow questions are semi-neutral

Green Count = The number of questions only one of the two students missed

In other words, the number of questions one student got right and one student got wrong

If students collaborate, we expect them to miss the same questions, so a high Green Count could be evidence against collaboration

Black Count = Red Count + Yellow Count + Green Count

In other words, this is the total number of questions at least one student missed

Why is this helpful? We’ll discuss it a bit later in this section

Recall from the earlier thought experiment that we can safely assume that the vast majority of pairwise comparisons are not cheating pairs. As a result, we can look at the distributions of the Red, Yellow, and Green counts across all pairs of students in the class as approximations of their null distributions (null hypothesis = “Red, Yellow, and Green Counts resulted from no collaboration”), and we can try to identify collaboration by looking at outliers of these distributions. The range of possible Red, Yellow, and Green Counts for a given pair of students is bounded by their Black Count (Black = Red + Yellow + Green), so we can do the following:

Plot the 2D distributions of Red, Yellow, and Green Counts (vertical axis) vs. Black Count (horizontal axis)

In other words, each pair of students defines 3 points: (Black, Red), (Black, Yellow), and (Black, Green)

Plot a given pair’s (Black, Red), (Black, Yellow), and (Black, Green) points

Check if the pair’s Red, Yellow, and Green Counts deviate significantly from what is expected at that Black Count

Estimate expected values based on the null distributions at that Black Count

Perform a statistical test to check for significance (e.g. Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test with 2 degrees of freedom)

An example plot of Red, Yellow, and Green Count distribution can be found in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4 Distributions of all pairwise Red, Yellow, and Green Counts vs. Black Counts in a 500-person Advanced Data Structures course (log-scale). 2D Kernel Density Estimates (KDEs) are shown as colored contours, and best-fit lines are shown for each distribution. A single pair of students with suspiciously outlying Red (9), Yellow (0), and Green (0) Counts for their given Black Count (9) is shown as a black vertical line with colored dots.#

I wrote a suite of Python programs to perform all pairwise Red Count, Yellow Count, Green Count, and MESS calculations, calculate a best-fit Exponential distribution, plot the distributions, and perform other downstream analyses, which is available as an open source project on GitHub. The tools in this repository support exams with multiple choice, short answer, math, Parsons, etc. problems: they simply perform string equality comparisons between responses to determine response equality.

Exam Response Timestamps#

Beyond just looking at similarities in exam responses, we can also look for interesting patterns in the timestamps of each exam response to detect collaboration [42]. In this subsection, we will discuss a few different patterns that one can look for when comparing the response timestamps between pairs of students. In practice, I personally typically first look for similarities in exam responses, and I then check suspiciously similar exams to see if there are interesting patterns in the timestamps, but these are two separate dimensions of signal of potential collaboration.

The most telling pattern between the response timestamps of two students is synchronization: if two students are submitting responses to the questions of the exam within seconds of each other, it is very likely that they worked together to answer the questions of the exam. Informally, you can simply take all exam response times for all students, sort them chronologically (e.g. this script), and manually compare pairs of students you may find suspicious (e.g. pairs of students that had suspiciously similar exam responses). Alternatively (or additionally), you can use a systematic approach to check for timestamp synchronization across all pairs of students in the class. One naive approach (which I have implemented inefficiently in this script) is to calculate a “Time Synchronization Score” for a given pair of students \(x\) and \(y\) as follows:

Define \(n_x\) and \(n_y\) as the number of responses from students \(x\) and \(y\), respectively

Note: Both values should ideally be equal to the total number of questions on the exam, but students might leave some questions blank (e.g. run out of time)

Initialize the Time Synchronization Score between \(x\) and \(y\) as \(S\left(x,y\right) = 0\)

For each submission time \(t_x\) from student \(x\):

Find the submission time \(t_y\) from student \(y\) that is closest to \(t_x\)

Add \(\left(t_x–t_y\right)^2\) to \(S\left(x,y\right)\)

For each submission time \(t_y\) from student \(y\):

Find the submission time \(t_x\) from student \(x\) that is closest to \(t_y\)

Add \(\left(t_x–t_y\right)^2\) to \(S\left(x,y\right)\)

Normalize \(S\left(x,y\right)\) by dividing by \(\left(n_x+n_y\right)\)

Note: In other words, we are calculating the Mean Squared Deviation (MSD)

You can then calculate this score across all pairs of students in the class, and then sort the pairs in ascending order of this score. In practice, every time I have done this, the students with the most synchronized scores (as per this score) also stood out with respect to the exam similarity detection methods described above, but some pairs of students detected via exam similarity did not appear at the top (reasons why will be discussed shortly). As such, this approach of detecting submission time synchronization is likely a decent complement to other methods of collaboration detection.

It must be emphasized that, while the existence of timestamp synchronization is strong evidence in support of collaboration, the lack of timestamp synchronization is not evidence against collaboration: it is simply uninformative. Namely, an extremely common form of exam collaboration (based on my own experiences over many years) is as follows: one student submits the exam first (potentially on their own, or working with the other student), and then the second student starts the exam after the first student submitted (potentially hours later) and submits answers obtained from (or in collaboration with) the first student. The exam timestamps between two students who collaborate in this manner will not appear synchronized: their exam times might not even overlap at all.

However, even in this scenario, not all hope is lost! Often times, when students collaborate in this manner, the second student will have extremely rapid responses (potentially for the entire exam, but commonly at least for decently large chunks of the exam). Thus, rather than comparing the two students’ timestamps, you can look at the time deltas between the later student’s (sorted) timestamps, and you can look for suspiciously fast sequences of exam responses. Xiao et al. [42] allude to this in their “Score-Time-Ratio”, which is a rate of earning points on the exam over time. I interpreted the “Score” (i.e., numerator of “Score-Time-Ratio”) to only include correct responses, and I would personally also suggest looking at “Response-Time-Ratio” (i.e., numerator being all submitted questions, regardless of correctness), as I have found many cases in which the copying student submits many incorrect responses in the burst of rapid responses.

LLM-Proof Problems#

All of the discussion about maintaining Academic Integrity in exams has focused on deterring and detecting collaboration, but it misses a common form of Academic Integrity violation that has skyrocketed since 2023: the use of Large Language Model (LLM) tools like ChatGPT to solve exam problems. While the unauthorized use of LLMs is largely a non-issue in in-person proctored exams (as the proctored environment can simply check for and disallow the use of unauthorized resources), it is a prevalent issue in online exams, even with the use of remote proctoring services.

While LLMs certainly pose a challenge in designing online exams, instructors can aim to write LLM-proof problems for their exams. Specifically, try to write problems that are hard to verbalize as a prompt. In my classes, I have a handful of problem styles that I look to use for this.

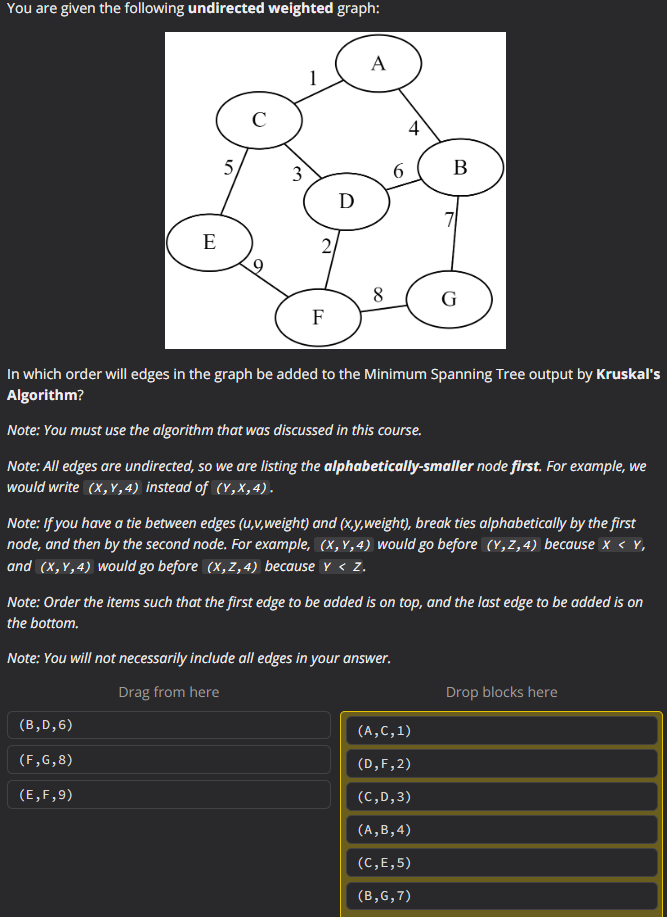

First, I like to write problems that ask about an image. In the Advanced Data Structures course I commonly teach, I like to post an image of a data structure that we have learned in class, ask them to execute some algorithm on the example in the image, and have them submit the results of the algorithm as their answer. In the current state of LLMs, it is non-trivial to design a prompt that relies on an image: the student would likely need to somehow translate the image into a text representation, which will be challenging and likely time-consuming (and thus problematic in a timed exam). While image-based problems will be easier to design in some disciplines vs. others, this approach is applicable to quite a range of subjects with enough creativity from the instructor. Note that image-based problems could pose an accessibility problem for students with visual impairments, so an instructor will want to have alternative forms of assessment if any students are incapable of seeing the image.

I also like to write problems that require some form of interaction with the problem. For example, in my Computer Science classes, I like to write Parsons problems, which are problems in which students need to drag-and-drop existing blocks of code to build a program. In my introductory programming courses, I like to write problems where the solution program is a non-standard approach to solving the computational problem (e.g. a somewhat convoluted way of finding the maximum of a list of numbers): the LLM will likely produce a solution that uses a simple approach (which will not help the student solve the problem), which makes the problem reasonably LLM-proof, and this type of problem requires students to think outside the box, which is a good assessment of mastery of the topic. I’ve also written questions that require the student to rearrange elements in some particular order to solve the problem.

Fig. 5 shows an example exam problem from my Advanced Data Structures course that demonstrates a problem that both (1) asks a question about an image, and (2) requires the student to interact with the web page to solve the problem.

Fig. 5 An example exam problem from an Advanced Data Structures course in which students are given the image of an example graph, and they are asked to rearrange some options to build the correct answer. This question is difficult to translate into an LLM prompt.#

Of course, these suggestions may become out-dated as LLM tools evolve (e.g. perhaps students will be able to simply screenshot the entire question and stick it into an LLM), but at present, based on the grade distributions of my exams (which disallow ChatGPT and similar, but I imagine students will try to use them anyways), they seem to be LLM-proof (otherwise the number of students who respond correctly would be much higher).

Programming Assignments#

Instructors of computing-related courses will likely want to maintain Academic Integrity on programming assignments.

Code Similarity Detection#

The most standard approach for maintaining Academic Integrity is to check for code similarity, and the most frequently used tool for this task (to my knowledge) is Moss [43]. Instructors can simply upload a collection of code files submitted by students, potentially including additional code files (e.g. starter code, existing solutions found on the internet, etc.), and Moss will generate a code similarity report. Moss is able to detect similarities even when minor trivial edits are made (e.g. changing variable/function names, rearranging lines of code whose orders don’t matter, whitespace and brackets, etc.), so it is fairly versatile to simple attempts at avoiding detection. The URL of the report will expire after ~2 weeks, so instructors can download a local copy as needed (e.g. using MossNet).

Glossary#

- Detection#

The act of correctly identify cases of cheating [24].

- Deterrence#

The act of stopping people from cheating [24].

- Moshiri Exam Similarity Score (MESS)#

An exam similarity score that increases in value as shared incorrect responses are more unique [41].

- Remote Proctoring#

A mode of exam administration in which students take the exam on a computer while being supervised by a person and/or computer software [24].