Niema’s Example Course#

Note

Source Code: teach_online/example.md

In this section, I will provide a complete example of one of the courses I commonly teach: UCSD’s CSE 100 course (Advanced Data Structures). Even if this exact recipe doesn’t work for the courses you teach, I hope that tidbits of the structure I use can give you some interesting ideas about how to structure your own courses. I will structure the subsections in this section by category of teaching-related task, and I will provide information about tools I use and how I use them to achieve the task.

Before I begin, I want to remind folks that this section is purely subjective: I am simply giving my own personal opinions. I am not sponsored by any company, and I will try my best to paint every platform as fairly as possible, and any positive or negative opinions I present about any platform should be treated exactly as what it is: my own personal opinions.

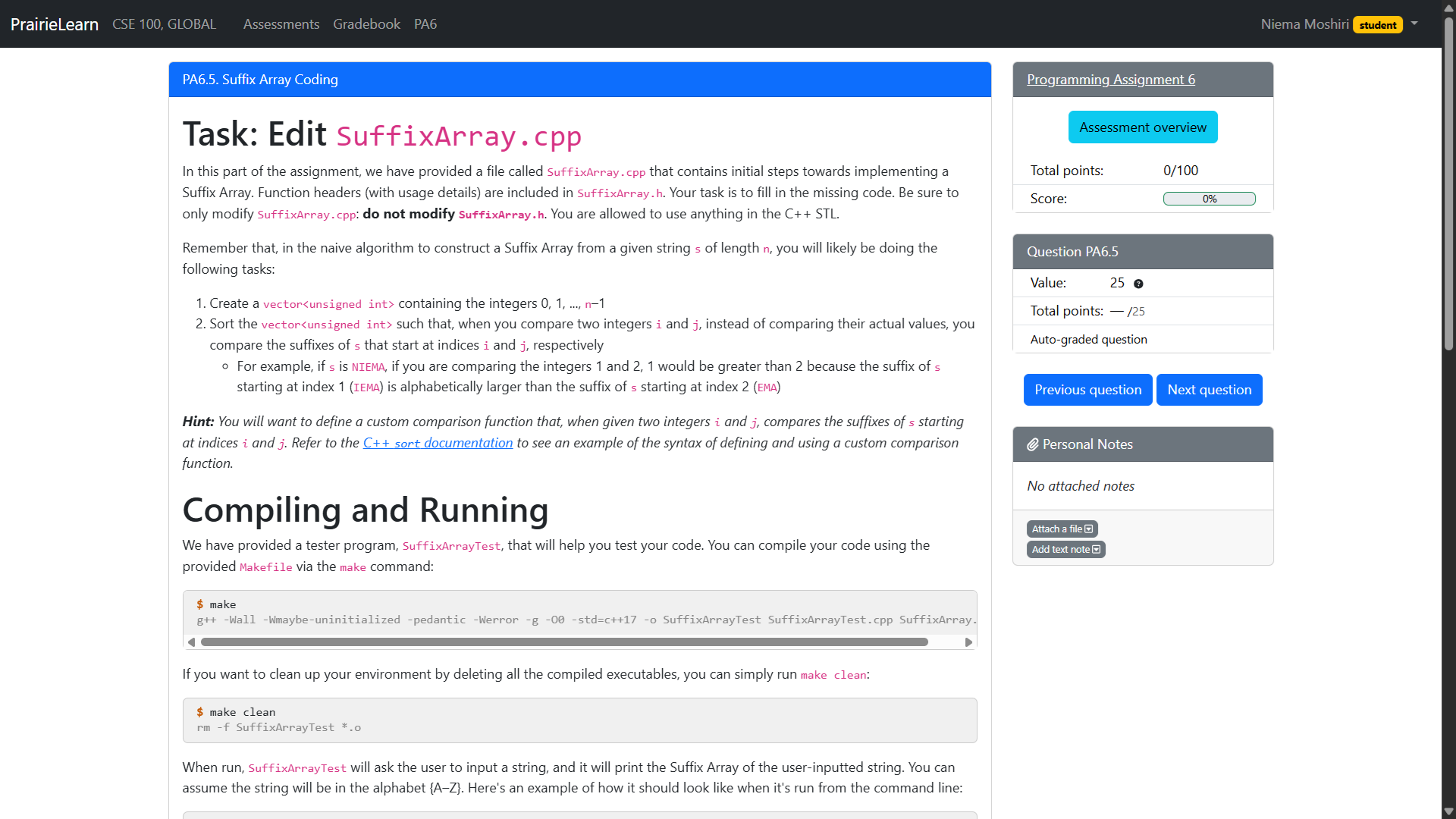

Assessments: PrairieLearn#

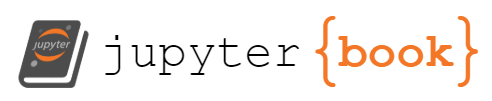

I host all of my course assessments on PrairieLearn. I briefly mentioned PrairieLearn in the Content Delivery section of this resource, but to expand and add some more specific details, PrairieLearn is an online platform that supports automatically graded assessments (including programming and exams!), and it supports randomization of every single problem type. If students bookmark my course instance within this single platform, they can keep up with all graded aspects of the course without needing to check anywhere else.

Fig. 6 PrairieLearn assessments from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Reading Quizzes (RQs)#

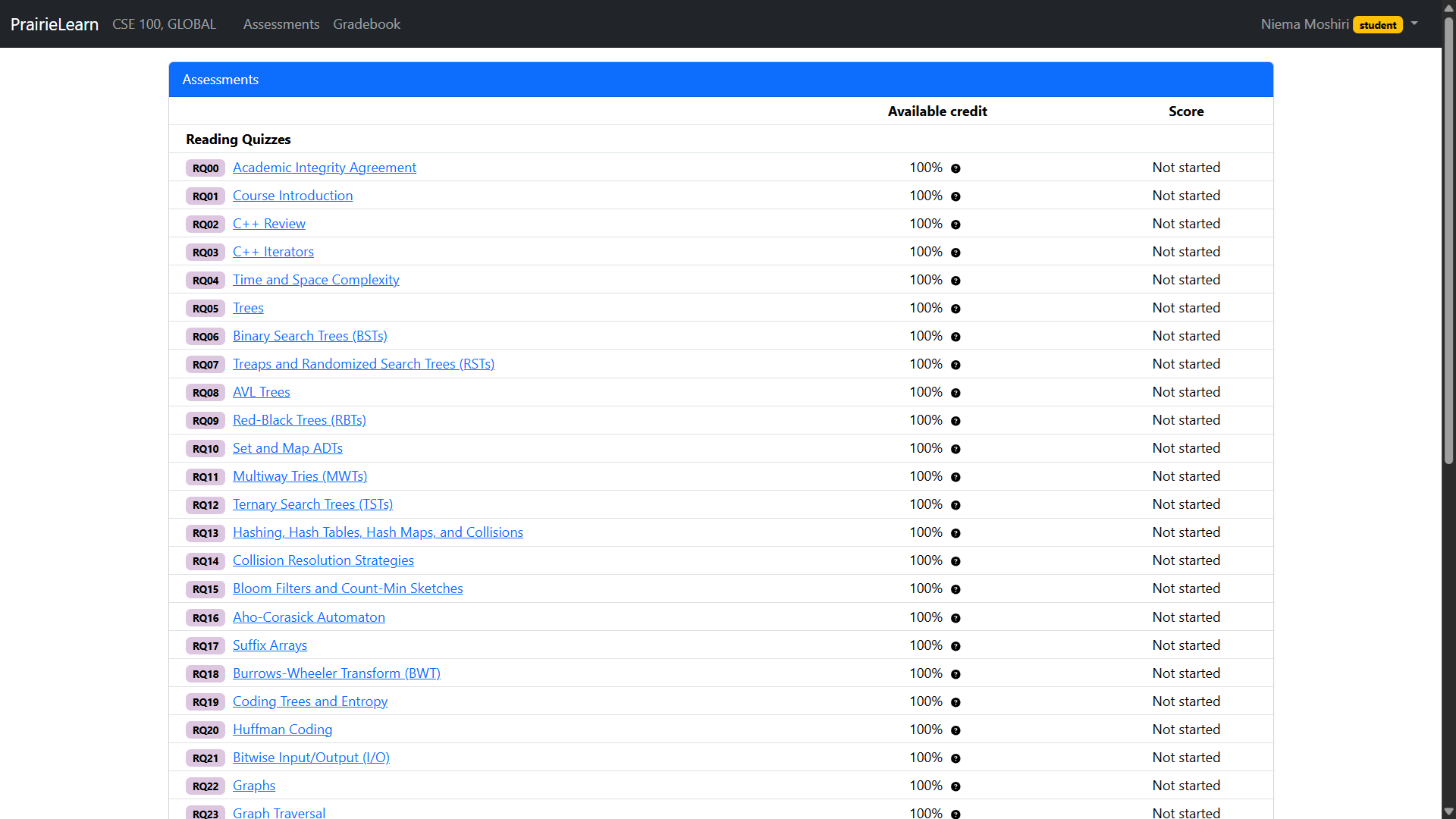

I have a Reading Quiz (RQ) due before every single day of class. Each is implemented as its own assessment on PrairieLearn. Each RQ typically consists of multiple non-coding questions about that day’s topic. I release all of the RQs for the entire course on the first day of class so that students can work as far ahead as they need to fit their schedule (e.g. frontload all of a week’s RQs the weekend before, work ahead to account for a big trip or expected absence, etc.).

Fig. 7 Reading Quiz from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

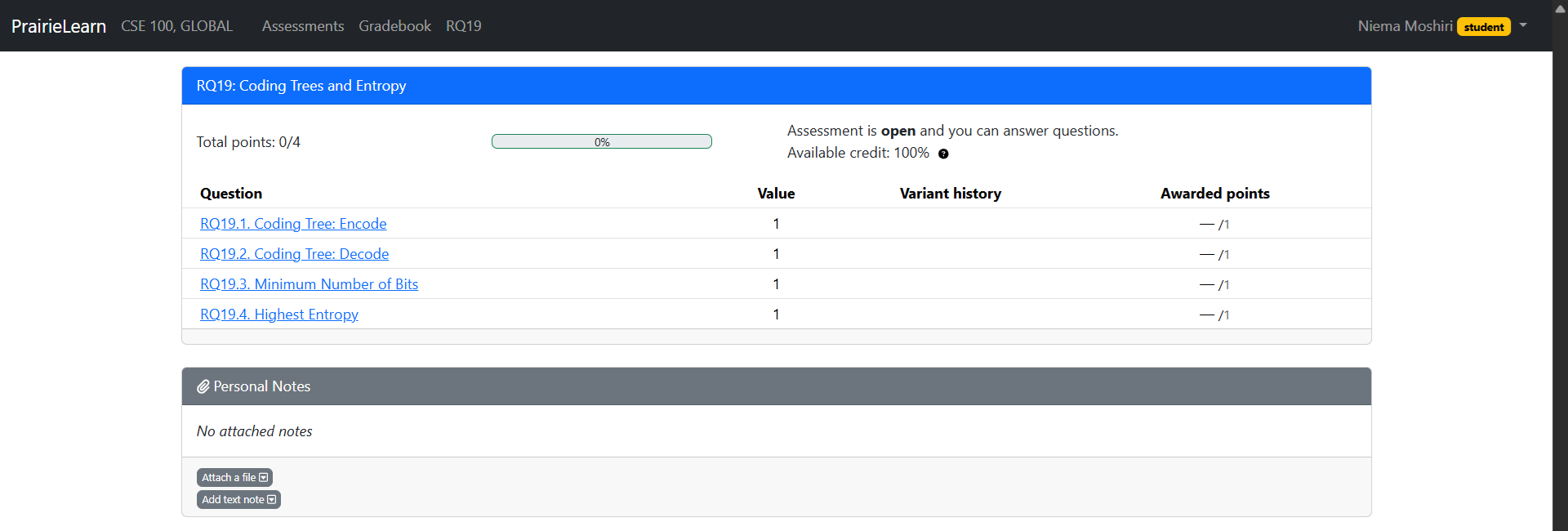

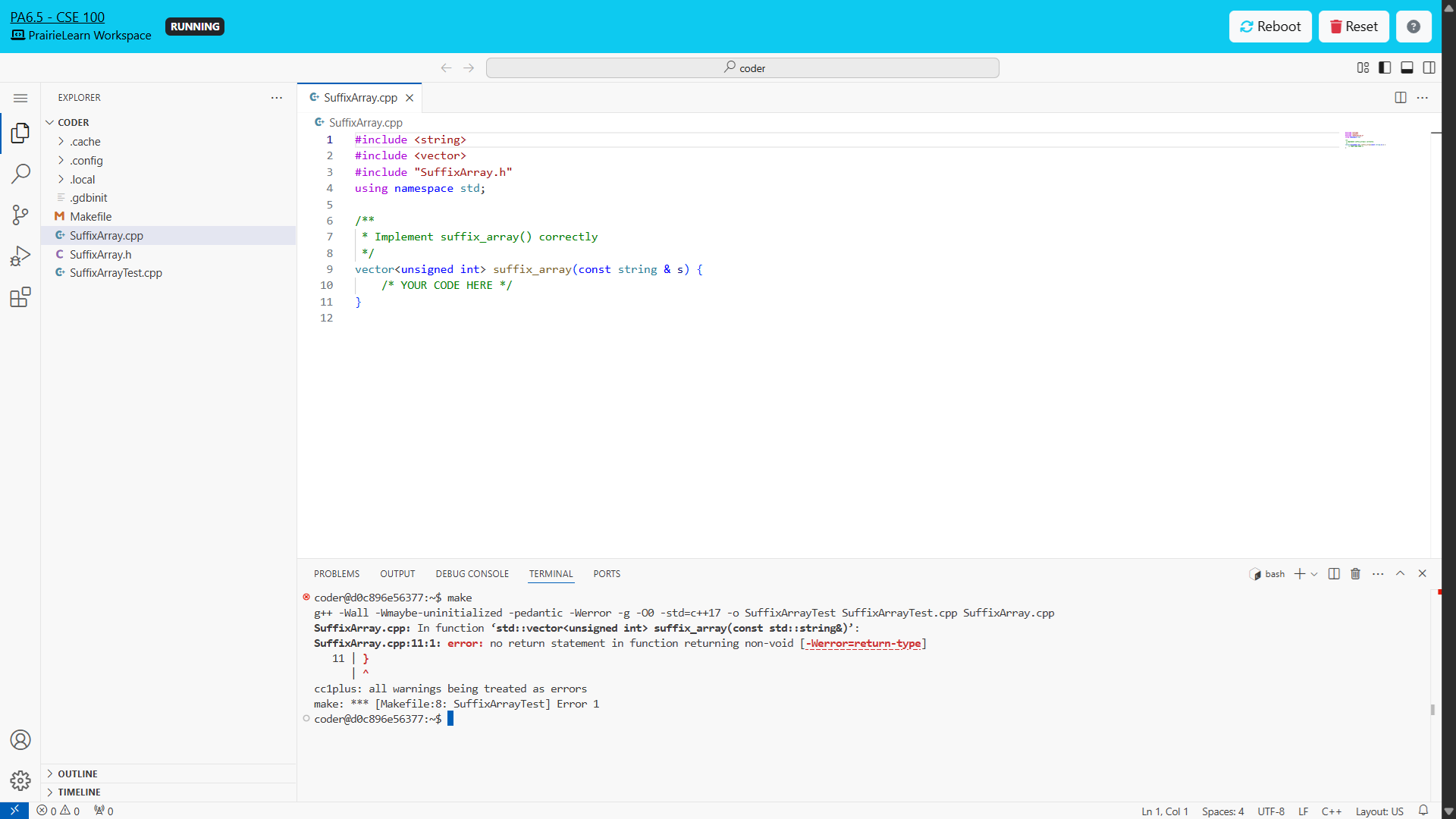

Programming Assignments (PAs)#

I have a weekly Programming Assignment (PA) for the first 6 weeks of class.

Each is implemented as its own assessment on PrairieLearn.

In coding questions on PrairieLearn,

students are able to write and run code directly within their web browser.

Students are given a VS Code-like code editing environment,

as well as a bash shell to compile and run programs

(or perform whatever bash tasks you want them to perform).

Importantly, this environment is configured via instructor-specified Docker image,

meaning the instructor can install any non-standard tools as needed

(this was especially helpful when I taught the Advanced Bioinformatics Laboratory course).

See the Dockerfile I used in this course.

Fig. 8 Programming Assignment from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Fig. 9 Coding question instructions from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Fig. 10 Coding environment for a coding question from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Projects#

My Programming Assignments (PAs) consist of fairly straightforward programming task (e.g. fill in the bodies of some functions), and as a result, it doesn’t require as much creativity and design from students. To account for this, in the last few weeks of class, I have two Projects, which are structurally similar to the PAs (write code to solve a problem), but which are much larger in scale and much more open-ended, requiring quite a bit of design from the student. Each is implemented as its own assessment on PrairieLearn.

Because the Projects are more open-ended and challenging, their instructions are much longer than those describing the PAs. PrairieLearn doesn’t support pagination in question instructions, so the question instructions on PrairieLearn point to a paginated write-up I host on GitHub.

Exams#

I typically administer two exams: one Midterm and one Final. Each is implemented as its own assessment on PrairieLearn. Because PrairieLearn questions can be randomized, every single question on both exams is pulled directly from a Reading Quiz (RQ) or non-coding question from a Programming Assignment (PA). I also create an ungraded “Practice Problems” assessment that contains every single RQ or non-coding PA question from the entire course, meaning students can generate as many practice problems as they’d like. This way, there are no surprises on the exam: students will have already seen every single question on the exam (just a different randomly-generated version of it), and they have even had the opportunity to practice every problem as many times as necessary to master it.

PrairieTest#

Because the exams are assessments implemented on PrairieLearn, they can be trivially administered via PrairieTest, which is PrairieLearn’s companion platform for exam administration. At UCSD, the Academic Integrity Office (AIO) runs a centralized in-person proctored testing facility named the Triton Testing Center (TTC), which inclues a Computer-Based Testing Facility (CBTF). As the instructor, I create the exam as an assessment in PrairieLearn (just like any other assessment), create a corresponding exam entry in PrairieTest, and then link the two. Once this is done, students can self-schedule each exam according to their own schedule constraints and preferences, without any need for manual intervention on my part.

A benefit of this form of exam administration is that I am able to administer proctored (and thus reasonably secure) assessments, but without forcing every student to take the exam at the exact same time: students still have the flexibility to take the exam at a date and time that fits their schedule. However, a major downside is that my online courses are no longer fully online: they require two in-person activities (Midterm and Final Exams). In the post-ChatGPT world, I think the benefit of enabling secured assessments coupled with the flexibility of self-scheduling outweighs the harm of having all assessments be insecure.

Behind-the-Scenes#

I don’t want this to be an in-depth walkthrough about how to implement course assessments on PrairieLearn, but I want to give a brief overview of how different components of a PrairieLearn course instance are defined.

Questions#

PrairieLearn’s questions-authoring documentation is dauntingly thorough, but I will summarize two general types of questions: non-coding and coding.

Non-Coding#

A single non-coding question is defined as a folder containing the following files:

info.json— Configuration file defining various options for this question (e.g. unique ID, name, etc.)question.html— HTML file defining how the question will be renderedTrivial randomization (e.g. shuffling Multiple Choice options) can be implemented here

server.py(optional) — Python script defining how to randomly generate an instance of the questionThis enables randomization of all aspects of a question (including HTML content!)

Coding#

A single coding question is defined as a folder containing the following files and sub-folders:

info.json— Same as non-coding questionsFor coding questions, there are additional options that need to be configured (e.g. coding workspace options, grading script, etc.)

question.html— Same as non-coding questionsworkspace(optional) — Files to exist in the home directory of the coding environment upon initialization (e.g. starter code, example data, etc.)

Assessments#

PrairieLearn’s assessment configuration documentation is also dauntingly thoroguh,

but in short,

a single assessment is defined as a folder containing a single configuration file (infoAssessment.json)

that defines various options for this assessment (e.g. unique ID, name, etc.).

Most importantly,

this file contains one or more question “zones,”

each of which contains a list of questions

that exist within that zone.

By default, students must solve every question in every zone, but the instructor can optionally define a number of questions to randomly be sampled in that zone. For example, each zone can correspond to a single topic in the course and can contain all of the questions related to that topic (e.g. 10 questions total), and the instructor can either require every student to solve every question (the default behavior), or the instructor can define a smaller number of questions (e.g. 5) to be randomly chosen from the total set of questions in that zone.

Course Instances#

A single course instance corresponds to a single offering of a given course, and it is defined as a folder containing one file and one folder:

infoCourseInstance.json— Configuration file defining various options for this course instance (e.g. unique ID, name, etc.)assessments— Folder containing all of the assessments of this course instance

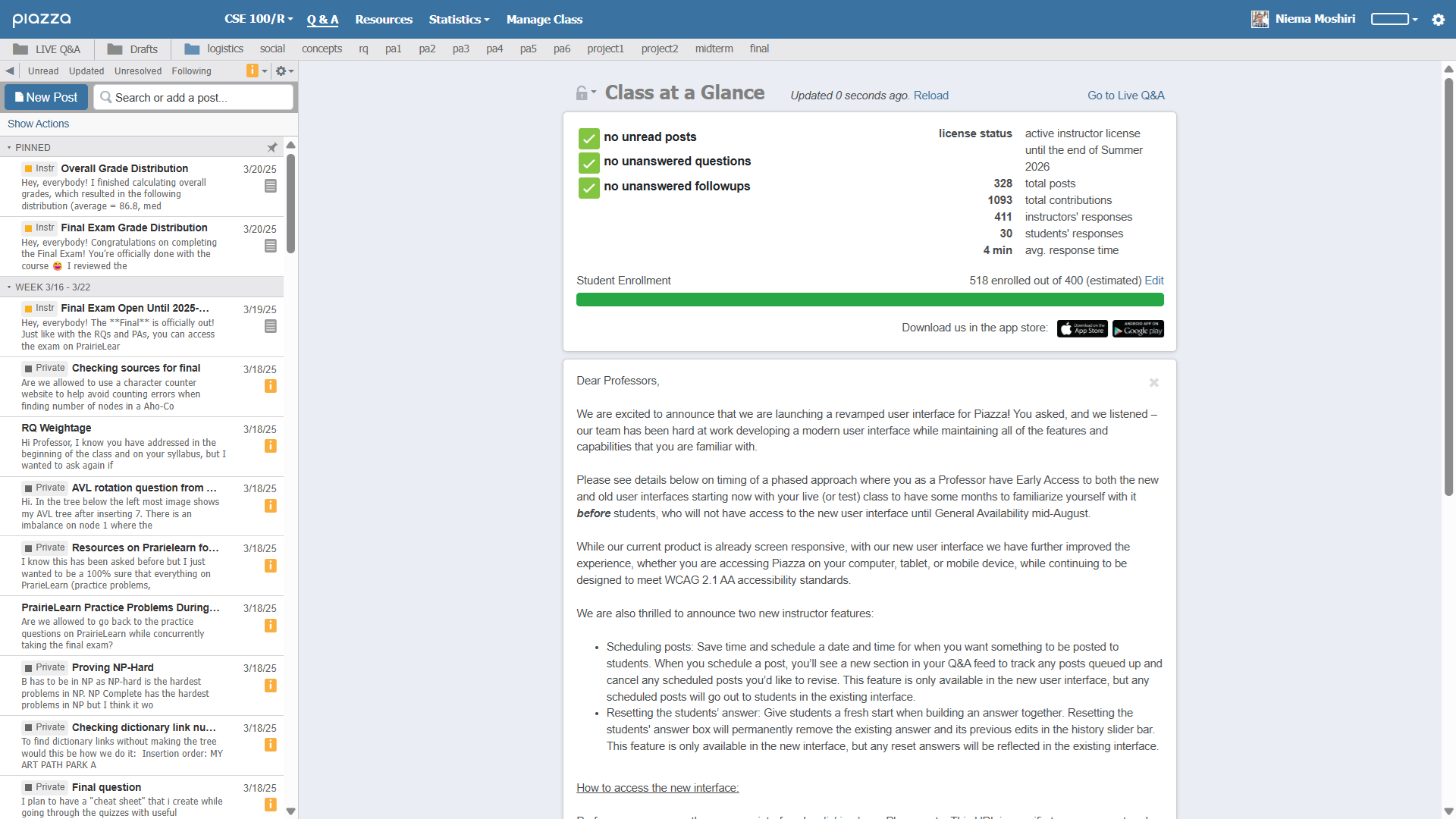

Discussion: Piazza#

I use Piazza as the discussion board for my class (Fig. 11). I personally strongly prefer Ed Discussion, as it’s much cleaner and more feature-rich in my opinion, but UCSD has a license for Piazza and doesn’t have a license for Ed.

Fig. 11 Piazza discussion board from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

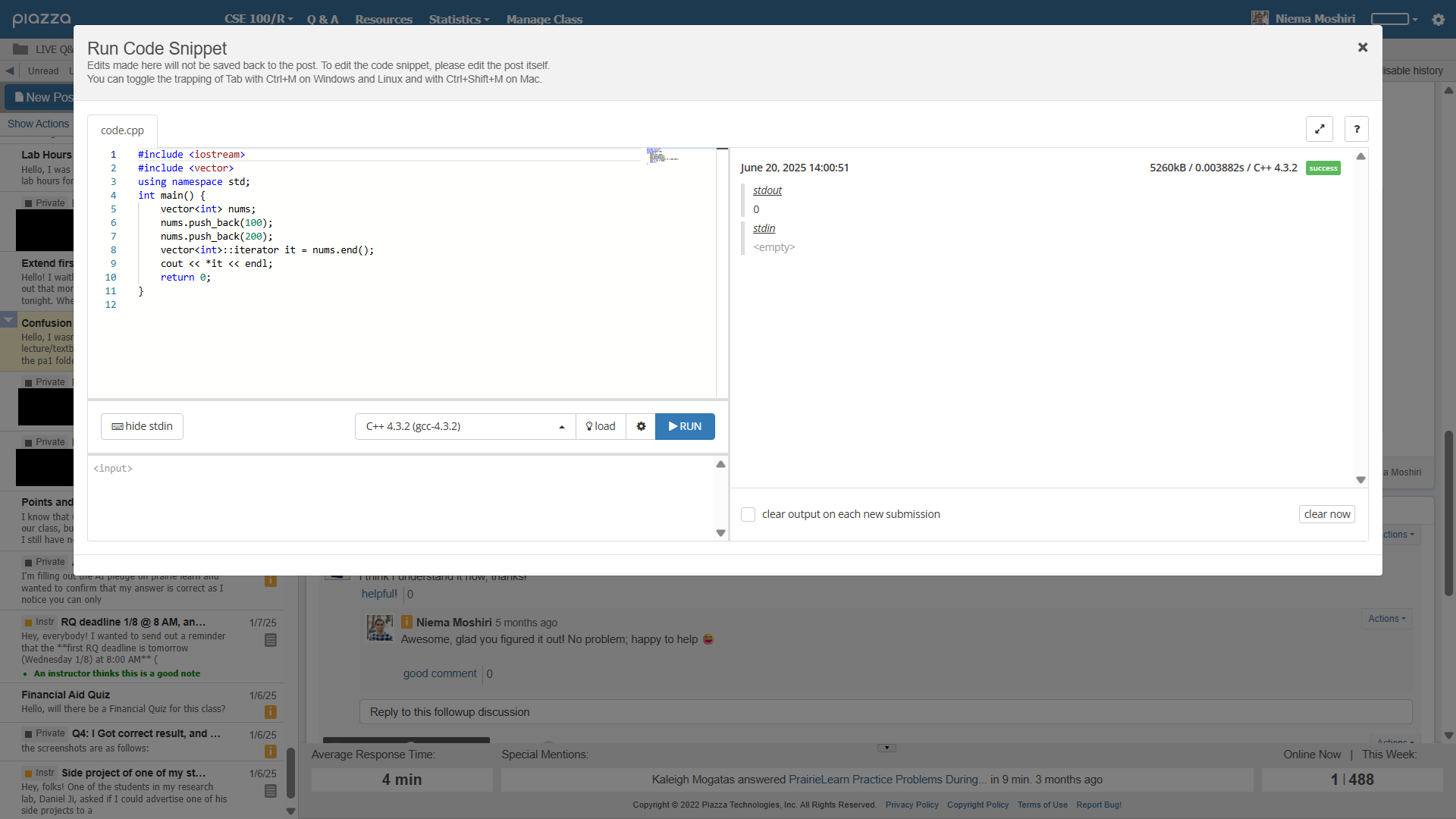

One particularly powerful feature of Piazza is that it supports the embedding of runnable code examples directly within a post (though Ed implements this feature much more nicely in my opinion). This has been absolutely game-changing in my Computer Science courses! When a student asks a question about some programming-related topic (e.g. about the programming language itself, or about a specific data structure or algorithm), rather than just answering the question with higher-level descriptive text, I can actually include runnable code examples within my explanation to enable the student to actually experience what I’m describing. The students don’t need to install anything other than a modern web browser: regardless of what device the student is using (e.g. laptop/desktop, tablet, or even phone), the student can simply click and run actual code directly in their web browser (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Ed Discussion post with runnable C++ code from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Course Calendar: Google Calendar#

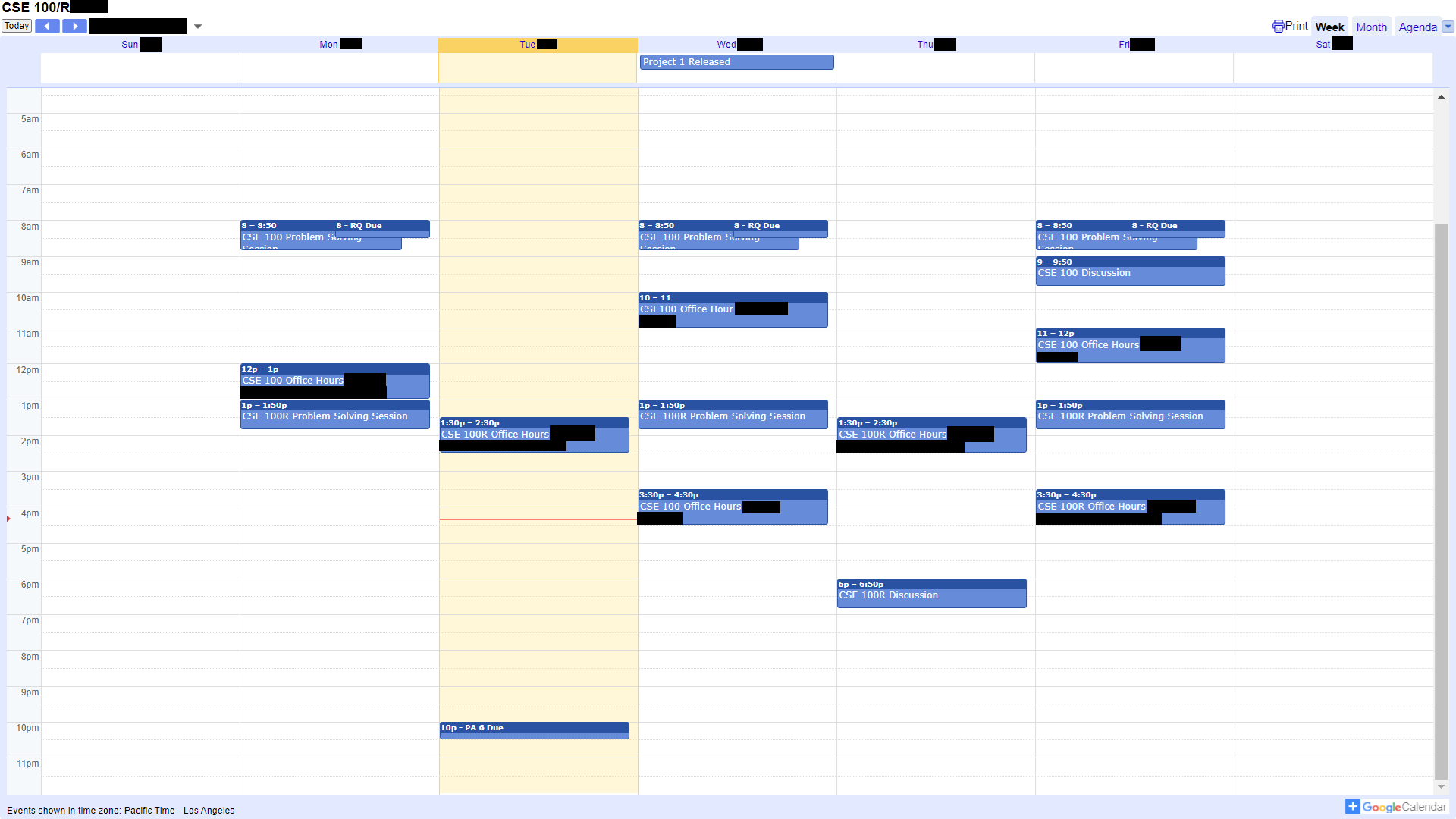

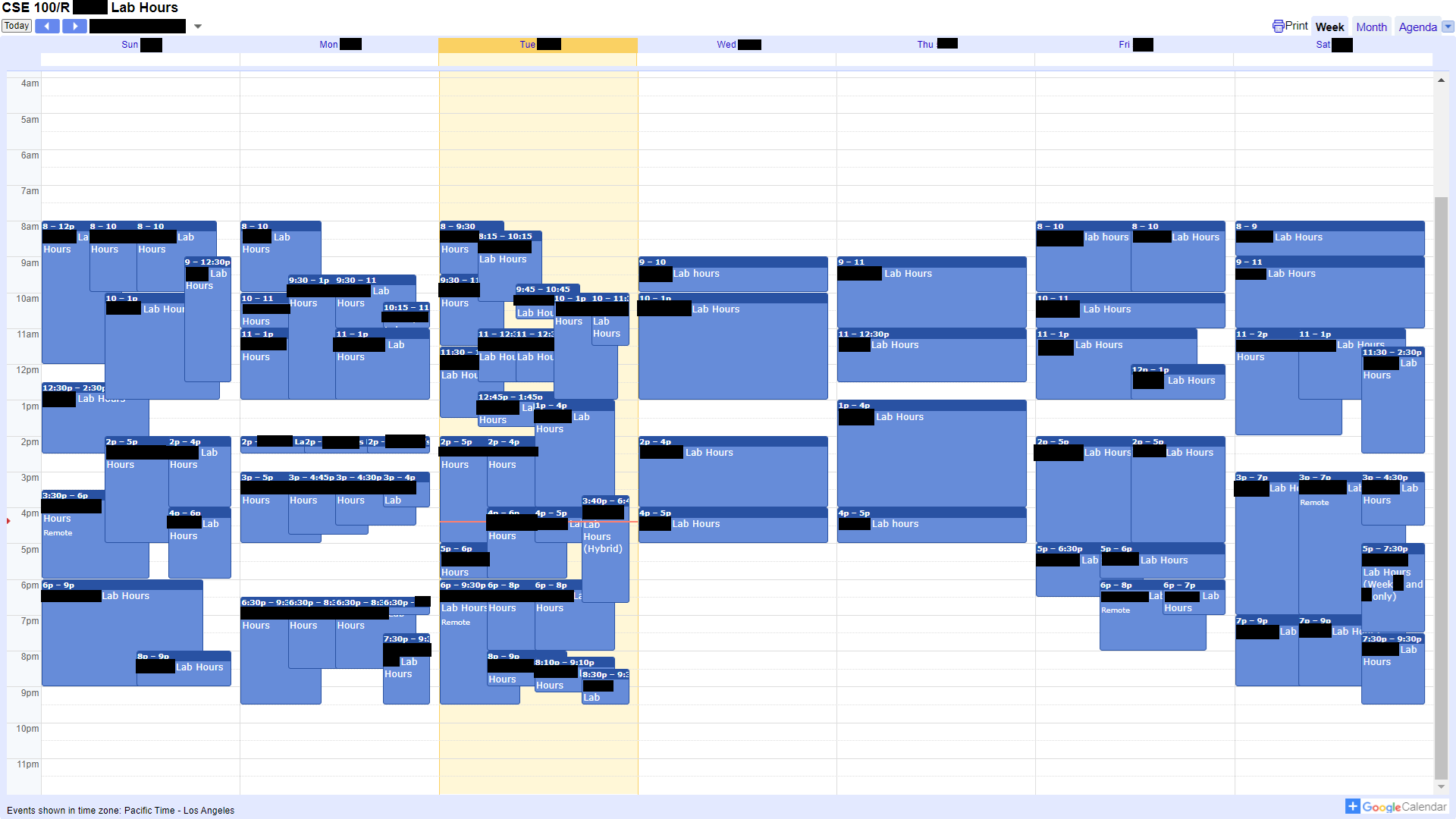

For keeping track of important course-related dates, I like to use Google Calendar. I typically create two calendars:

A “main” calendar that contains synchronous class sessions, instructor and graduate TA office hours, release dates, deadlines, and exams (Fig. 13)

A “lab hours” calendar that has all drop-in office hours that are held by undergraduate instructional assistants (Tutors) rather than instructors/TAs (Fig. 14)

I like to use Google Calendar because it’s easy to manage, share, and embed, and students can easily subscribe to the Google Calendar and have it sync with their laptop, phone, tablet, etc.

Fig. 13 Main calendar from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Fig. 14 Lab Hours calendar from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

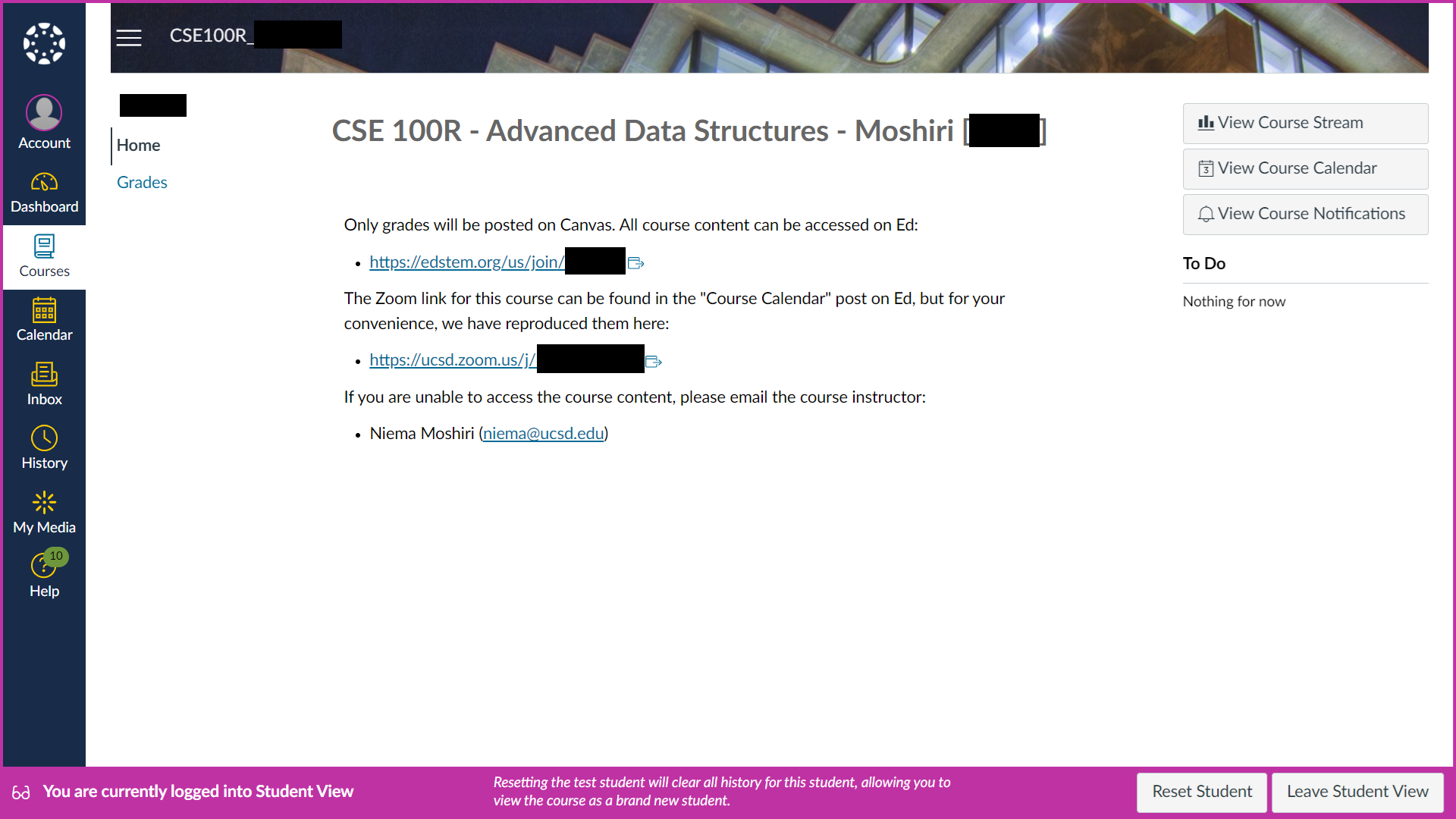

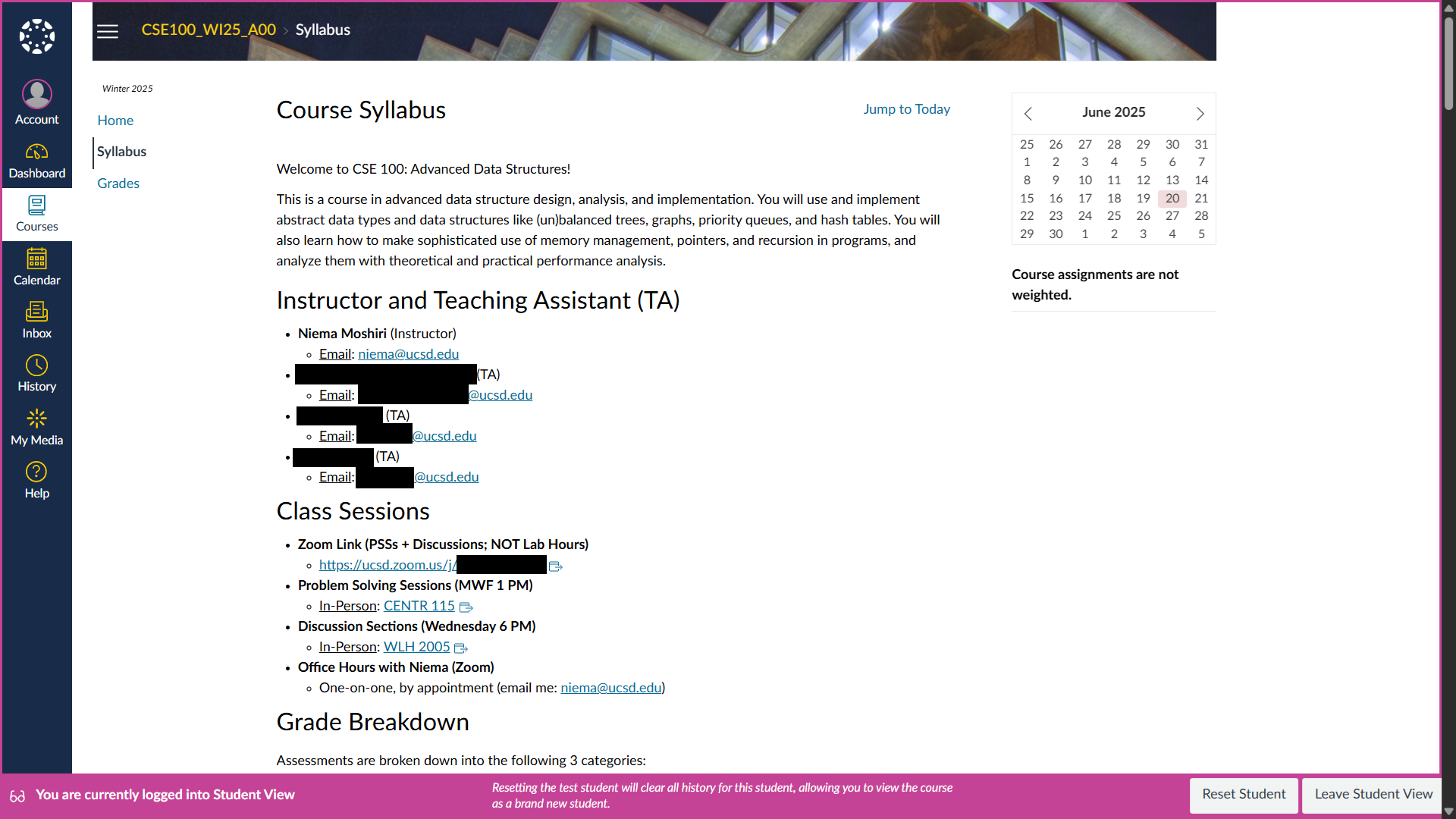

Learning Management System (LMS): Canvas#

I teach at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), and UCSD uses Canvas as its official Learning Management System (LMS). I’m not sure about the specifics of UCSD’s policies regarding the use of Canvas, but my department has recommended that instructors should use Canvas as a landing page for students: when students enroll or waitlist in classes at UCSD, they automatically get added to the course’s Canvas page, but there is no additional notification or communication to the instructor and student. In order to address both matters (the recommendation to use Canvas, and the fact that Canvas is the only landing page newly-enrolled/waitlisted students can see), I use my class’s automatically-generated Canvas course to serve three purposes:

The Canvas “Home” has links to important resources, such as PrairieLearn and per-topic instructional instructional materials (Fig. 15)

The Canvas “Syllabus” page contains all relevant information about course logistics (Fig. 16)

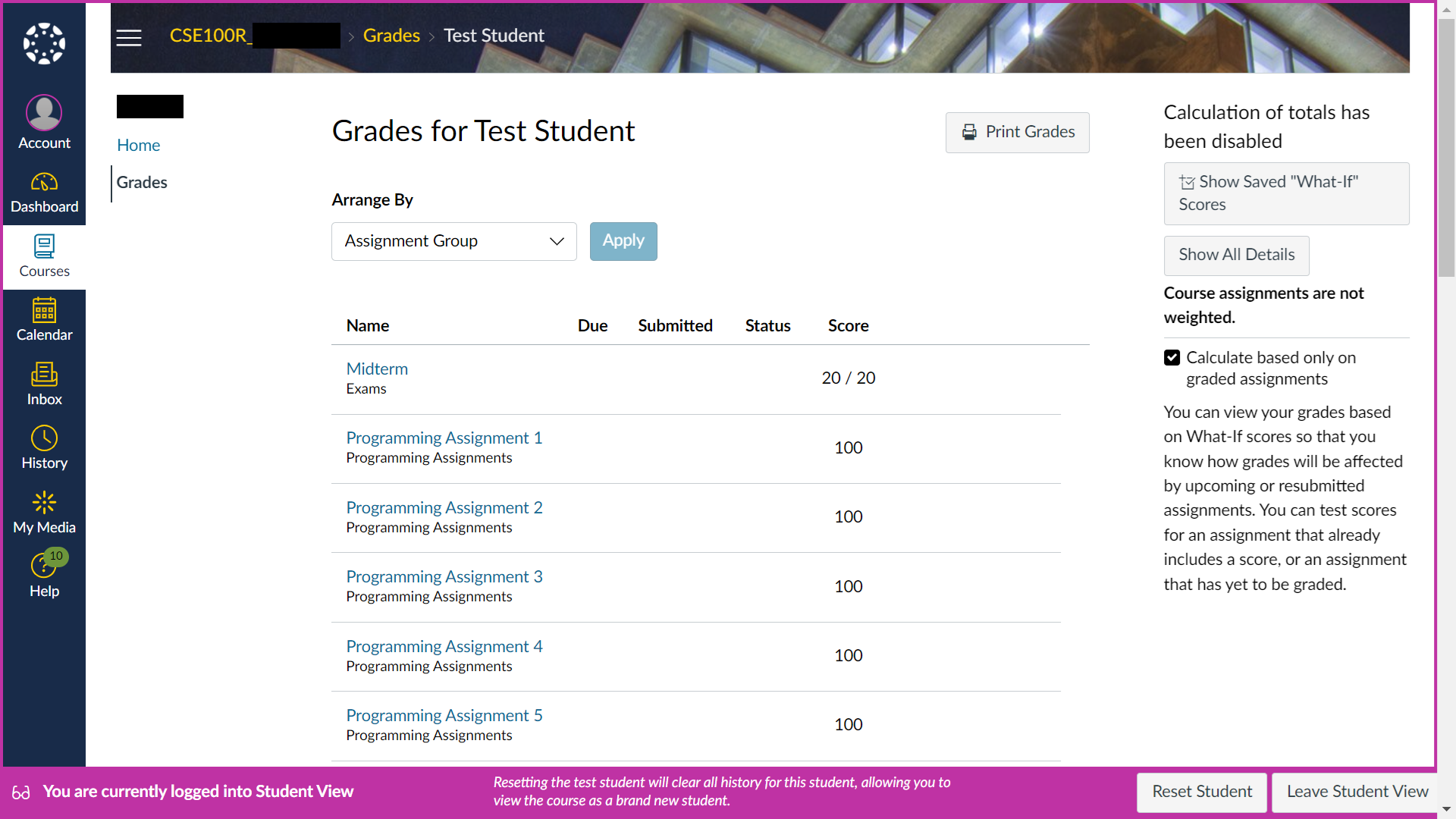

The Canvas “Grades” page serves as the official gradebook for the class, regardless of what students see on PrairieLearn (Fig. 17)

This is to handle extensions/accommodations, grading corrections, etc. that may not perfectly align with the points shown on PrairieLearn

Fig. 15 Canvas “Home” page from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Fig. 16 Canvas “Syllabus” page from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Fig. 17 Canvas “Grades” page from an example Advanced Data Structures course.#

Video Conferencing: Zoom#

I teach at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), and as was the case with most universities during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, UCSD gave all instructors an institutional license to use Zoom for teaching, meetings, etc. Even after in-person instruction at UCSD resumed, all UCSD employees still have an institutional Zoom license, so I continue to use it in my online teaching. Even if UCSD didn’t have an institutional Zoom license, I would probably still use Zoom because it does everything I need it to do quite well:

I have a single recurring Zoom link for each course, which I have set to automatically record to the Zoom cloud

I use the same Zoom link for all of my lectures as well as my TAs’ Discussion sections for simplicity

I like to use the (classic) Zoom whiteboard feature with a Wacom tablet to hand-draw/write during class

This is absolutely critical for the live problem solving I like to do in my classes

The screen sharing functionality works quite well, and I love that I can annotate directly on the shared content

I also like that I can choose between sharing my entire screen vs. sharing just a specific window

It has nice security features to prevent unwanted disruptions (e.g. password-protected meetings, waiting room, etc.)

Video Distribution: YouTube#

As I mentioned in the Video Conferencing: Zoom section of this resource, I like to use Zoom’s “automatically record to the Zoom cloud” feature to record my synchronous class sessions. I don’t require synchronous attendance in my classes (see the HyFlex section of this resource for some rationale), so I need some way of distributing class recordings to students (even if I required synchronous attendance, I would still distribute recordings to students for review). I prefer using YouTube to distribute all videos in my courses for the following reasons:

YouTube automatically captions all videos

This is critical for students who have hearing impairments or who don’t speak English natively

The automatic captions aren’t perfect, but they can easily be manually corrected in YouTube Studio

You could even use the automatic English captions to create captions in other languages

YouTube automatically reencodes all videos to multiple resolutions

My classes are recorded in 1080p resolution, but these files might be too large to stream smoothly on a poor internet connection

YouTube has a 1080p resolution stream, but it also reencodes the video to 720p, 480p, and 360p

YouTube Studio supports trimming and cutting videos directly in the browser

As a result, I can trim out the quiet parts of the recording from before/after class

I can also cut out silent parts in the middle of class (e.g. when students are working on problems)

YouTube has unlimited capacity

My institution uses Google Drive for cloud storage, but each account has a 100 GB capacity

I can easily share recordings with future students or reuse them in other ways